Perkus Tooth dealt in occult knowledge, and measured with secret calipers

Jonathan Lethem’s 2009 novel Chronic City concerns the friendship between Chase Insteadman, a former child actor turned idle New York celebrity, and Perkus Tooth, a writer and critic who spends most of his time in his walkup apartment, surrounded by the cultural ephemera he has used to construct a universe. Perkus’ pantheon is that of many socially maladjusted aesthetes – Cassavetes, Chet Baker, Norman Mailer. He prefers the samizdat to the official – bootleg CDs, movies taped off TV onto hand-lettered VHS.

Perkus is a clear and acknowledged stand-in for Paul Nelson, the writer and critic who taught Bob Dylan about folk music when they both still lived in Minnesota, signed the New York Dolls to Mercury Records, and maintained an uneasy friendship with Clint Eastwood over many years and interviews. Lethem was friends with Nelson and uses the Perkus character as both homage and refraction into the book’s weird alternate universe of Pynchonian character names and seemingly endless virtuality. (The fact that it was published shortly before smartphones and social media ate the universe give it a prophetic heft upon rereading.)

Chase is the narrator but Perkus is the focus. He is simultaneously an object of pity and a guru. His diet consists of hamburgers, coffee and marijuana, his health and hygiene are barely maintained, but for Chase he seems to promise access to a world more real than the one the former actor can lay claim to. “The horizon of everyday life was a mass daydream – below it lay everything that mattered,” Chase decides after a day spent with Perkus.

Throughout the book, Perkus acts on the assumption that if you give the right cultural artifact the appropriate amount of attention, if you draw the right connections between the right artists and their works, something will be revealed, something maybe even the original creators neither intended or understood. This will all pay off eventually, he believes. I am sympathetic to his interpretive fugues, having spent enough of my life sifting my own chosen artifacts for my own arcane revelations. Frequently that consideration has rested on the music of Pere Ubu.

We only pretend to live on something as orderly as a grid

Pere Ubu are from Cleveland. This statement is salient on two levels: as an objective geographical fact, and as an ongoing, deliberate mode of being, a crucial point of differentiation from the idea of being from New York, or Los Angeles, or London. The actual membership of the band may have resided nowhere near Cleveland for decades. But Pere Ubu are from Cleveland.

Cleveland in the mid-1970s was home to a thriving underground rock scene, almost completely unknown to the rest of the world at the time. Bands like the Electric Eels and Rocket for the Tombs, which became Pere Ubu, mutated the apocalyptic groove of the Stooges – as if the Michigan band’s DNA had oozed east, from Ann Arbor to Detroit, around Lake Erie to Cleveland. It wasn’t so much as if these bands had nothing to lose – they had nothing to gain. No one was paying attention. It seemed that no one got into, or out of, Cleveland until Rocket from the Tombs split into two units. The Dead Boys took the RFTT showstopper “Sonic Reducer” and a more accessible (relatively speaking) approach to New York’s punk scene, where they quickly scored a deal with Sire Records, of Ramones and Talking Heads fame. The other half formed Pere Ubu, stayed in Cleveland, and put out their own records.

Those early records, a clutch of singles and a searing 1977 debut album, are where many people get on and off the bus. At that point, the band still bore the imprint of Peter Laughner, an early member who left before the first album was recorded and died at age 24, leaving behind only oft-bootlegged (and recently compiled) home recordings and live tapes for devotees to scrye and treasure. Laughner is not referenced in Chronic City, but is the kind of gnomic hipster Perkus would obsess over.

Starting with 1978’s Dub Housing, singer David Thomas became the band’s organizing conceptual force. The outsider narratives of the early songs were replaced by fragmented lyrics that reflect a sort of bewilderment at the contingent wonder of the modern world, like a rust belt David Byrne. On 1979’s New Picnic Time he kicks things off by yelping “It’s me again!” as if he was surprised but delighted to find himself on your turntable. Thomas can be an imposing presence in interviews, but on record his off-kilter sprechstimme is strangely charming, once you acquire the taste.

Thomas’ cryptic lyrics, coupled with the sheer breadth of his body of work – I count 17 Pere Ubu albums, 11 solo, and a basket of collaborations, live releases and other miscellanea, inevitably create a giant puzzle for those willing to take a step back and try to apprehend the whole. Recurring themes, lyrical motifs and obsessions (film noir, Brian Wilson, the golden age of American highway travel) create the impression that the entire thing will cohere into some kind of answer if you just listen the right way, at the right time, in the right order.

The chaldron testified to zones, realms, elsewheres

In the second act of Chronic City, Perkus, Chase and their confederate Richard Abneg, a renters’ activist turned mayoral fixer, become briefly but intensely obsessed with chaldrons, a form of austere ceramic vase that provokes an almost hypnotic ecstasy in the three (to be fair, they’re stoned on high grade weed in Perkus’ apartment most of the time – the book’s title holds multiple meanings). The chaldron temporarily becomes a receptacle that can hold all of Perkus’ obsessions, streamlining his usual manic intellectual zigzagging. The joke, and the warning sign, is that none of them actually encounter a chaldron In Real Life – they commune with JPGs on eBay auctions they repeatedly fail to win, as the prices are repeatedly driven into five figures by mysterious bidders. It’s only when Perkus wanders off at a holiday party at the home of New York’s Mayor Arnheim, the book’s Bloomberg stand-in, that he learns the truth about the chaldrons, which precipitates a personal crisis and the book’s third act.

A secret masterpiece is always best. It changes the world slightly

By 1982, Pere Ubu had lost its original guitarist, Tom Herman, and drummer, Scott Krauss. They were replaced, somewhat improbably, by the avant-garde journeymen Mayo Thompson and Anton Fier.

Thompson had formed The Red Krayola in Houston in 1966, a band so out there that the hoary cliche “ahead of their time” must be pressed into service. Thompson went to England in the ’70s, finding common cause with the avant-garde collective Art & Language. Many interesting figures passed through the Red Krayola/Art & Language cross-pollination, including Pere Ubu sound wizard Allen Ravenstine, post-punk saxophone colossus Lora Logic, and even filmmaker Kathryn Bigelow (a constellation point that would have delighted Perkus).

Anton Fier, whose Ubu cred must have derived in part from being a native Clevelander, has served time in the Feelies, the Lounge Lizards, the Voidoids, collaborated with Bill Laswell and Bob Mould, and founded the Golden Palominos. One can only hope his memoirs are in the offing.

You don’t add such distinctive players and not change the DNA of your band fundamentally. As such, The Song of the Bailing Man is an album short on tunes and punk aggression but packed with distinctive moments, like watching strange birds flit by while you travel through a foreign country. “On the long walk home/thoughts stride long and crankily,” Thomas drawls on the album’s opening song, and the rest of the record could be the sights seen on that long walk. Petrified dinosaur bones, a thunderstorm, boats crossing Lake Erie. And on “Horns are a Dilemma,” the final song, the punchline is that home is nowhere to be found. “As we roll out to sea/we’ll need to rely on ingenuity,” Thomas muses, maybe hoping you forgot what he said about getting home. Geography is a crucial element in Thomas’ songwriting; his characters need to know where they are, precisely situated even in an imaginary landscape. By the same token, their recordings tend to be extremely spatial; each element of the music is distinct on the soundstage. On “Horns,” we can hear voice, drums, bass, guitar, electronic squiggles, and trumpet arranged almost in a straight line, with Tony Maimone’s bass closest to the listener and both Thomas’ vocals Eddie Thornton’s trumpet furthest away. Maybe they left without you.

Pere Ubu would go silent for 5 years, then reconstitute more or less permanently in the late 80s for an unlikely run at the college rock charts. They released a new album this year titled The Long Goodbye, named for the Raymond Chandler novel, a favorite of Perkus Tooth. As John Peel said of the Fall, they’re always different, always the same. They’re like a cup.

Look at me, I’m in tatters

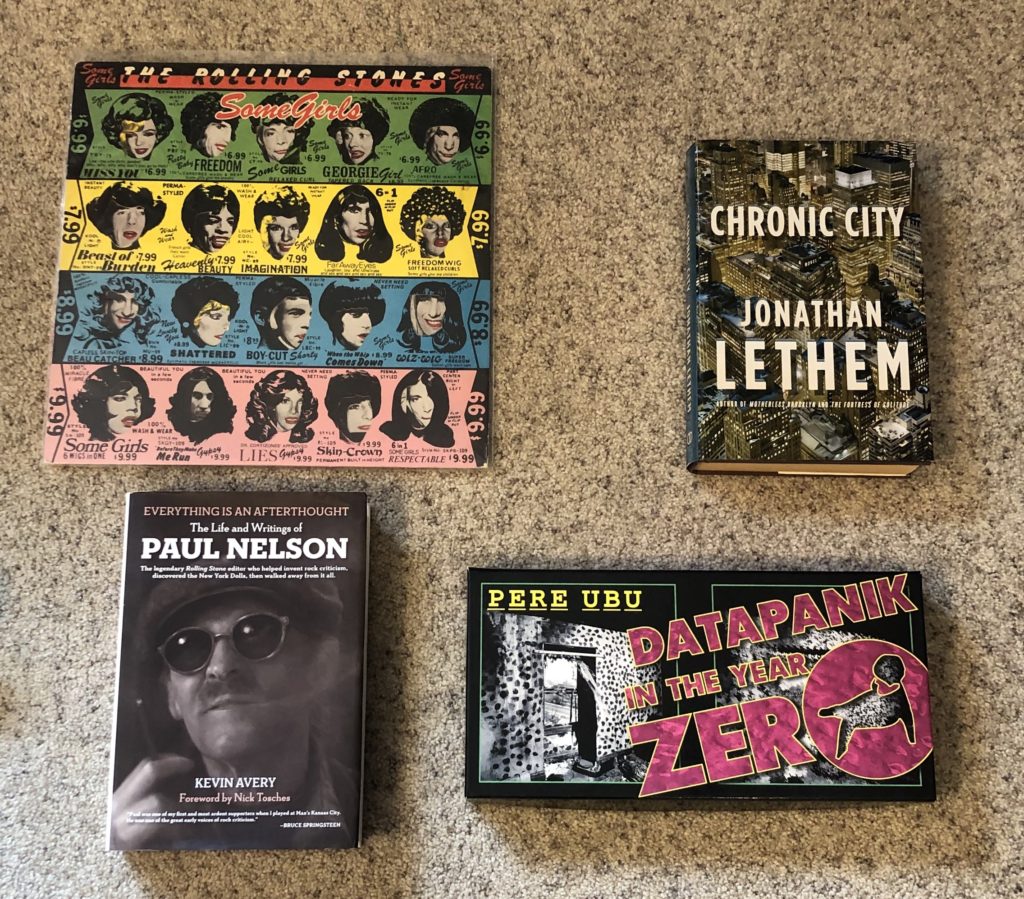

Perkus begins the final section of Chronic City squatting in an apartment building for dogs, divested of his possessions but for a record player and a copy of the Rolling Stones’ Some Girls. Disabused of the notion of the chaldrons’ significance, he plays and replays the album’s last song, “Shattered,” trying to extract latent significance from Mick’s punk-disco ramble, a song whose most prominent lyric is “Sha-doobie.” (Lethem refers to “the corroded jape” of Keith Richards’ guitar, a turn of phrase too poetic for the narrator, but too good to pass up for the novelist.) A giant tiger roams the streets of Manhattan. Chase’s fiancee, an astronaut trapped in orbit, writes letters to which he can’t reply. What does it all mean?

The world inside the world

Six months ago, as I was being wheeled into an operating room to have my gall bladder removed, I heard Mick Jagger singing “Beast of Burden” over the OR speakers. What a good omen, I thought in my drugged stupor, the surgeon clearly loves the Rolling Stones, and is playing Some Girls while she preps. As the song faded, I expected to hear “Shattered,” the next song on the album. I thought of Perkus Tooth, as I always do when I’m about to hear that song. Instead, a Journey song started playing, and even in my haze I realized with disappointment they were just listening to a classic rock station on the radio. Then I was unconscious.