It was late 1983, and Jonathan Demme was licking his wounds. He had spent the previous 10 years slowly building a career in Hollywood, at one point graduating from “producer of a Roger Corman women-in-prison movie” to “director of a Roger Corman women-in-prison movie.” His critical breakthrough, 1980’s Melvin and Howard, led to a gig directing Goldie Hawn in Swing Shift, a WWII-era homefront drama that had success written all over it. But post-shoot creative differences between Demme and Hawn led to a delayed release date and a final cut that didn’t involve Demme. The movie limped into theaters months late, in Spring 1984, with the screenwriter’s name removed at her own request. Critics and audiences shrugged, and the movie made back less than half its budget.

But in December ’83, the movie wasn’t out yet, and Demme was locked out of the editing room. Despite this setback, his mood was probably enhanced by the fact that he was already working on his next movie. He spent four nights that month at the Pantages Theater in Los Angeles, shooting concert footage of the Talking Heads.

I’d like to introduce the band by name

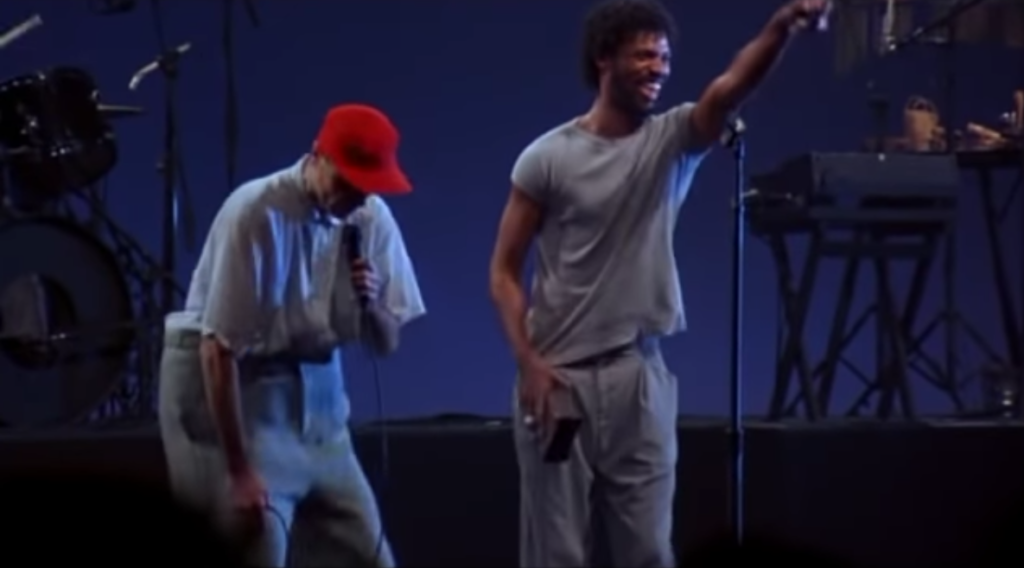

If Demme’s luck was bad on Swing Shift, it couldn’t have been better on this project. He had aligned himself with a great band at the absolute peak of their success. Talking Heads were the only members of the CBGB’s class of 1976 who would make it to the mid-80s with both their spirit and commercial prospects intact. Blondie broke first, but flamed out fast; Patti Smith had retreated to family life in Detroit; the Ramones were spinning their wheels. David Byrne, Tina Weymouth, Chris Frantz and Jerry Harrison kept absorbing new influences, developing gracefully, and scoring a #9 hit and a gold album in September of 1983 with “Burning Down the House” and Speaking in Tongues. The accompanying tour showcased an expanded band, including the incomparable Bernie Worrell on keyboards and Brothers Johnson guitarist Alex Weir.

Stop Making Sense, the movie made from those shows at the Pantages, is a concert film – the first of many over Demme’s long career. (Actually, Demme said it was a “performance film,” to distinguish it from a “concert film” like The Last Waltz, which was tied to a specific concert event.) But it’s not necessarily accurate to call it non-narrative. The show famously begins with just Byrne walking onstage with an acoustic guitar and a boombox, opening with the band’s early song “Psycho Killer.” From there, the lineup slowly grows – Weymouth joins on bass for the 2nd number, then Frantz on drums, and so on, until the entire lineup is arrayed in all its power, unleashed on an astonishing repertoire of songs about postmodern dislocation. Byrne’s lyrics are often caricatured as the ultimate in middle-class white-guy alienation, but the music played by the expanded lineup reveals the universality of his songs, and gives the lie to the ethnocentric chauvinism behind the idea that only WASPs might ask questions like “How did I get here?”

It probably would have been difficult to make a bad movie out of these shows, but Demme elevates the great to the sublime. He certainly understood the power of the close-up – we’ll be talking about that soon – but his specialty is the human body, the way it moves and the way it interacts with other bodies and its environment. In that sense he had an ideal subject in Byrne, who is not a dancer as such, but a very compelling mover. Byrne has discussed the movie’s “narrative” as being the slow freeing of the singer’s spirit – from his stumbling, frightened lurches during the concert opener, to the joyful scream he lets loose during the climax, a cover of Al Green’s “Take Me to the River.” The set pieces in the middle of the show dramatize this development. I particularly regret the way the famous “big suit” has been reduced to a slide in a familiar montage of 80s quirk; along with the Fred Astaire-inspired dance with a floor lamp, they illustrate the band’s pop detournement, taking objects so mundane you don’t even notice them – a suit, a lamp – and knocking them slightly askew.

It’s tempting to overcomplicate it, and I probably have already. Ultimately, it’s a stunning set of songs filmed by a kindred spirit, in a manner that highlights and emphasizes their strengths. To call it a great concert film is to undersell it; it is moving, accessible, and endlessly rewatchable. It is not just the greatest concert film, it is my favorite movie.

Let’s go out and have some fun

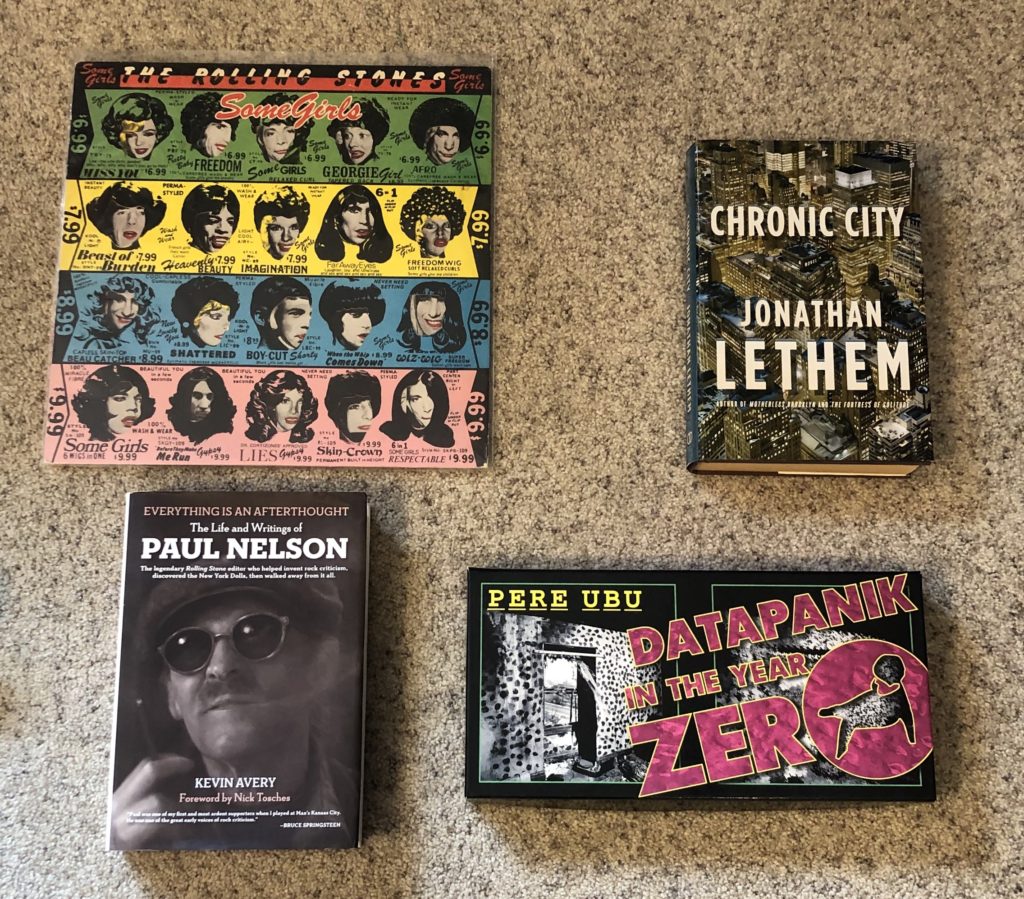

An ocean away, another quartet who emerged from the wreckage of punk were also having a very good year. New Order had released “Blue Monday” in March 1983 and watched it become the biggest-selling 12-inch single of all time. The music that followed that year and next – the album Power, Corruption and Lies, and the non-album singles “Confusion,” “Thieves Like Us” and “Murder,” cemented them as the ultimate coalescence of post-punk guitar music and the emerging synthesizer and drum machine-driven dance scene. It also definitively thrust them out from the shadow of Joy Division, the moody, epochal band that 3/4 of New Order had founded, a group which had been seemingly poised to take over their corner of the world before singer Ian Curtis committed suicide in May 1980.

If Talking Heads’ music in 1983 represented a reconciliation of punk alienation with the big tent approach of 80s boomer pop, New Order were still chilly and distant; their humor, when it appeared, was of the pitch black variety that belied their working-class Mancunian origins. Their third album, 1985’s Low-life, seemed like a capitulation of sorts: photos of the band, previously verboten, appeared on the album packaging, and two album tracks were released as singles (the band’s first 8 singles didn’t appear on an LP until the 1987 compilation Substance). The first single, “The Perfect Kiss,” is where Jonathan Demme rejoins our story – he was selected to direct the video.

The song continued the project that “Blue Monday” started – a compelling merger of dubby post-punk with the electronic dance music that had emerged from New York and Detroit and found surprising purchase in New Order’s home city of Manchester, culminating in the so-called “Second Summer of Love” in 1989. “Perfect Kiss” includes typically gnomic lyrics from guitarist and singer Bernard Sumner, alluding to mysterious and possibly violent events happening just off the edges of the song. It also includes an excellent use of sampled frog croaks.

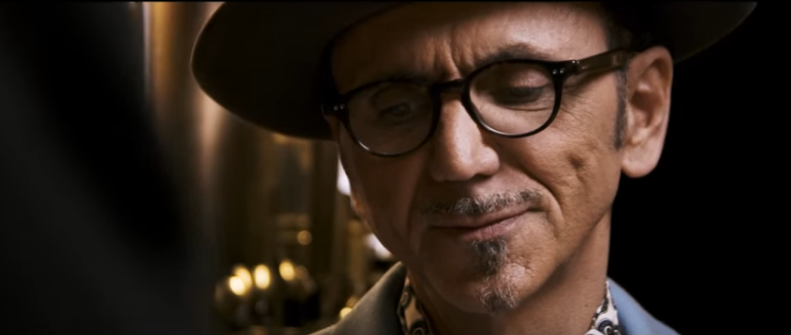

Typically for the band, the clip subverts many of the standard tropes of the pop music video. To begin with, it’s not a mimed recreation of the song’s released single recording; it’s a live in-studio take. It also blows past the 5-minute time limit that might have resulted in MTV airplay; clocking in at 10 minutes 40 seconds, it was unlikely to be seen widely until a home video release. The video is filmed almost entirely in static close-ups of the band’s faces and hands; when the camera finally jumps back at the halfway point to show an establishing shot of the band in their performance space, it feels unaccountably dramatic.

The song is structured like dance music, consisting of a slow accretion of different parts: first drum machine, then a melodic bass line, then sequencer, then keyboards, and so on. Demme uses a signature trick he adopted in Stop Making Sense, picking close-ups for maximum expressiveness instead of keyed to solos or other “big” moments. So we get Gillian Gilbert patiently waiting to start the sequencer, Sumner bobbing his head to get the tempo, Steven Morris’ apprehensive grimaces throughout, and Peter Hook’s dead-eyed take-it-or-leave-it stare into the camera at the end.

The result feels almost pedagogical – follow along at home and you, too can play like New Order! – and its ascetic seriousness would come across as pretentious if both the group and the filmmaker were not operating at such a high level. Demme and New Order were still possessed of a certain just-outside-the-mainstream cool, a situation that would change for both in the next decade. In 1985, it feels like the right person capturing the right band at the right time. It is my favorite music video.

If there’s a common thread throughout much of Demme’s best work, it’s community and collaboration, the belief that we can accomplish more together than separately. A rock band or a movie set can represent an almost utopian collaboration; the tragedy of Swing Shift is both artistic and professional, because the re-cut film emphasizes the star over the ensemble, and the seizure of the film by its producers denied Demme an opportunity to collaborate on the finished product. I’ve never been in a band or made a movie, but I’ve been lucky enough to work with groups of people who were all committed to working for something bigger than themselves, and perhaps that’s why I find his brand of pragmatic positivity so affecting.

And at the end of it all, Demme is a fan, an enthusiast. There is an audio recording of the performance captured in the “Perfect Kiss” video, featuring studio chatter from after the take. The director’s voice breaks the uncanny silence following the performance. “That was amazing!” enthuses Demme. “Whooooa, that was good!” Finally a voice from the control room intercom is heard, interrupting his gushing: “Should I cut, Jonathan?” The director comes back to himself. “Oh sorry, yes!” Cut.