“Bob Dylan 1970” was released on Friday, with such little fanfare – it appears that it’s skipping the streaming services for now – that I might have forgotten about it entirely if I hadn’t pre-ordered the CD. A pleasant Friday evening surprise on my doorstep, then – an enjoyable afterthought suited to the copyright-related deck-clearing the 3 CDs represent.

It’s humorous that Dylan, Inc. has an “official” Bootleg Series, now 15 volumes strong, yet still finds cause to sneak out archival releases that don’t quite make the cut for the series proper, usually comprehensive tour box sets that only obsessive suckers (hi) would spend time and money on. “1970” is a different animal, more of a retroactive appendix to 2013’s “Another Self Portrait,” the 10th volume in the Bootleg Series. It wasn’t until the following year’s Basement Tapes box set that they started releasing expanded box sets alongside the more traditional, tightly curated 2-disc editions. If the 6-disc format existed when “Another Self-Portrait” came out, the music on “1970,” drawn from the same sessions, would presumably have been included.

Many, including myself, found “Another Self Portrait” a revelatory release – although I’ve always enjoyed the loose, mythos-deflecting music on the original “Self Portrait” and its follow up “New Morning,” something about the slightly less fussed-over recordings, and the juxtaposition of the outtakes from both records, somehow felt closer in spirit to what may have been intended – a contemporary approach to a folk record, a way to emerge from the other side of the ’60s with lessons learned, but jettisoning the Byronic artist persona that may have required bodily mortification to fully escape from.

The 2010s saw the emergence of a new kind of archival release, the mega box set of “complete sessions,” purporting to provide the complete picture around a landmark album’s genesis. Naturally bootleggers pioneered this approach long ago, but the idea of take after take of the same song seeing official release long seemed far-fetched. I’m Old Enough To Remember when the Stooges released a 7-CD box set chronicling the “Fun House” sessions in 1999 – at the time, it seemed almost willfully perverse – 28 takes of “Loose”! (In another sign of the times, last year the collection was reissued as a preposterously expensive 15-LP vinyl box set, completing the original album’s evolution from dirtbag burnout classic to bookshelf fetish object for the wealthy. It might be offensive if you didn’t consider it a balloon payment to Iggy for godfathering much of the best rock music of the last 50 years.)

As a self-confessed obsessive sucker, I’m fascinated by these releases, and the different creative modes they portray. One of the more obvious candidates for such a comprehensive treatment was the Beach Boys’ lost magnum opus, 1967’s “Smile,” which was finally reassembled and released in 2011, along with 4 and a half CDs of session outtakes. What you hear on “The Smile Sessions” is a jigsaw puzzle being constructed in the studio by Brian Wilson. His polite exhortations have a brittle edge to them, enhanced by what we know of the breakdown and retreat that were soon to follow. He isn’t exploring, or even collaborating in the traditional sense – he’s already got the music in his head down to the last detail, and the recording process is just the final step in the artistic supply chain.

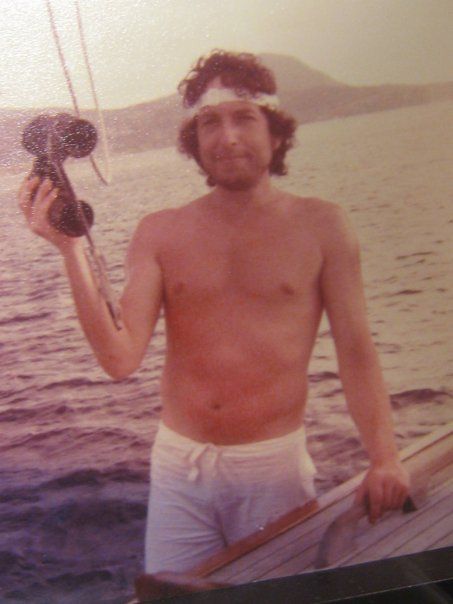

Dylan, needless to say, had a more informal relationship with the recording studio. His recent entries in the Bootleg Series, expanded to include hours of outtakes, portray this to a sometimes comical degree, such as on 2018’s “More Blood, More Tracks” the six-disc collection drawn from the “Blood on the Tracks” sessions. The early, abandoned recordings feature just Dylan on his acoustic guitar, accompanied by the loud, distracting clacking of his sweater’s buttons on the back of his instrument. Asked about this years later, assistant engineer Glenn Berger said “People wonder why didn’t Phil [Ramone] say ‘Bob, you’ve gotta take your vest off, or move the buttons aside.’ It may seem weird, but we were in kind of a multiple state, awed and freaking out and scared. It was intense.” I’ve often been nonplussed by rock musicians’ propensity to go shirtless or semi-shirtless, but perhaps there’s a practical reason for it.

2015’s “The Cutting Edge” compiles sessions from 1965 and 1966, which produced possibly his most feted LPs – “Bringing it All Back Home,” “Highway 61 Revisited” and “Blonde on Blonde.” For obvious budgetary reasons, I had to settle for the 6-CD compilation, although an 18-CD edition collecting every take from every session was also released, presumably to sit on custom-made shelving alongside the Stooges box set. (As it happened, I scored my copy by taking a flier on an eBay seller in China with a very agreeable price – if it’s pirated, it’s very convincingly done.) What we hear on these sessions is Dylan learning to work with a band for the first time, and realizing many of his performing tics won’t fly when you have to play in rhythm with other musicians. (Granted, he’s spent the last 30 years of live performance exploring just what it means to play in rhythm with other musicians.) When it’s just Dylan and his guitar, he was free to smear vocal lines unevenly across multiple measures, confident his self-accompaniment would catch up with itself. When beholden to a rock rhythm section, the initial results can feel constraining – you can feel the push and pull on Take 13 of “Stuck Inside of Mobile,” where his vocals are, well, stuck inside the marching band rhythm, contrasted with the master (Take 20)’s elastic lope, which reconcile the band’s electric propulsion with his singer-songwriter’s expressiveness. So much of the so-called folk-rock of the 70s and beyond used this template, and it’s easy to forget that it was largely invented, on the fly, by Dylan and his session band in Nashville – and you can listen to it as it happened.

Which brings us back to “1970,” after Nashville, after “Judas,” after the motorcycle crash and the Basement Tapes. Dylan had retreated geographically and psychologically from the cutting edge, in a sense never to return. He always claimed he never offered what people seemed to want from him, and from now on he’d only give what he chose. If there’s nothing on “1970” that improves on “Another Self-Portrait,” that’s only logical – the initial release was clearly designed to present the best of the spring and summer sessions. But the fact that the three discs are as enjoyable as they are demonstrates what a laid-back roll Dylan was on that year. Rejecting the personal and artistic struggles of the previous decade, there will be no more staying up for days in the Chelsea Hotel, just an ongoing, freewheeling conversation with the American songbook. New songs don’t need to outdo the covers, they can sit comfortably alongside each other in a continuum. George Harrison’s laid-back noodling represents something of a path not taken for the Quiet Beatle’s next few decades – his professed detachment from the material world often seemed to come through gritted teeth, sucking the joy out of his music – ironically until he reconnected with Dylan toward the end of the 80s.

“1970” embodies those three words that will always make me sit up straighter – For Completists Only. There’s really no reason you need to hear a skeletal, quickly discarded run-through of “Ghost Riders in the Sky,” followed by a cowboy lope through Sam Cooke’s “Cupid.” This is largely inessential music, given a perfunctory release to protect expiring intellectual property rights. I find it delightful.